The migration numbers game

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Given the rambunctious immigration debate in countries around the world, it is tempting to believe that the globe is awash with migrants.

Whether it is the heated debate in the US over President Barack Obama’s move to normalise the status of some 5m illegal migrants or the wriggling of political elites in response to the rise of anti-immigrant parties in Europe, it is hard to find a country in the rich world where immigration does not sit near the top of the political agenda.

There are certainly signs that, as the global economy recovers unevenly from the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis and the economic malaise that followed, some migrants are seeking opportunities in those countries where the recovery is strongest. Britain last week reported that net migration reached a record 260,000 in the year to June 2014, a result derided by critics as a government failure and hailed by business groups as a needed tonic for a recovering economy.

But, viewed globally, the situation is neither as simple nor as new as the heat in the political debates might have you think. In fact, when you consider the data, migration today looks more like an odd paradox of globalisation than a consequence of it.

We live in a globalised world in which the opportunities for mobility are much greater than before. However, the reality is that we are just as prone to stay home as we were half a century or more ago. There are more migrants today than there have ever been – more than 232m, according to the UN. But then there are more people in the world than at any other time.

Today, as was the case in 1960 and as has largely been true for the five decades since, just 3 per cent of the global population live outside the country of their birth.

“Why is it that 97 per cent of the world population doesn’t migrate, at least internationally?” asks Mathias Czaika, a researcher at Oxford university’s International Migration Institute.

“The phenomenon is not migration. The phenomenon is non-migration.”

That, he argues, should be at the core of the political debate. But politics have always been volatile in economic downturns and history tells us that migrants have often been targets for the disgruntled when economies slow.

The reality is that migration in history tends to track economic opportunity and that this time is no different.

According to UN data, there are now a million less migrants in the world each year – 3.6m on average in recent years – than there were before the crisis. According to the OECD, the number of migrants seeking jobs in its predominantly rich member countries almost halved from 4.4 persons per thousand population in 2005-08 to 2.6 persons per thousand in 2009-2012.

Illegal migration, often driven by a search for economic opportunity, also appears to have slowed in recent years in the US and Europe. In the EU, illegal immigration has fallen largely as a result of the expansion of the union and the drawing in of countries such as Romania that had at one time been big sources of illegal migrants.

People continue to flee conflict: more than 3m people have registered as refugees from the war in Syria alone. But the great migrations today are taking place inside countries rather than across borders.

China has 200m more urban residents than it did a decade ago and plans to house 100m more migrants from rural areas in its cities by 2020. The world as a whole now has a little over 230m international migrants and added 77m between 1990 and 2013, according to UN data. There is a vast difference in rate also. China is urbanising at a rate of 1.8m new city residents each month, according to the World Bank. The US, which remains the biggest destination for immigrants, gains just over 1m new legal immigrants each year.

Spend some time looking at the data and it becomes clear that politicians may be having the wrong immigration debate.

Global movement: Steady flows

There are more people living outside their home country than ever, with the UN classifying 232m people as international migrants in 2013. But that is largely a result of population growth. Since 1960, the percentage of the global population classified as migrants has remained steady at roughly 3 per cent.

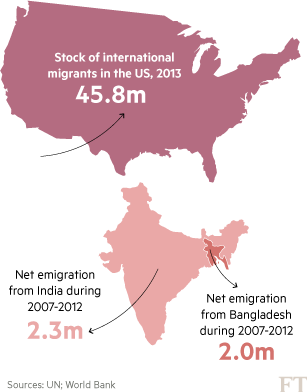

Arrivals and departures: American dream reigns while Indians and Bangladeshis lead exodus

The US remains by far the biggest destination for migrants. There are now almost 46m people in the US classified as international migrants, or one in six of the population. India and Bangladesh have been the biggest net exporters of people in recent years.

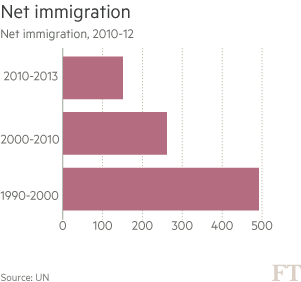

Crisis takes toll: Slowdown restricts movement

The crisis of 2008 had a big impact on migration, with a million fewer people a year moving to another country on average after 2010 than in the 10 years before, when the average was 4.6m, according to the UN. Average net migration between OECD countries fell to 2.6 persons per thousand in 2009-12, according to the OECD.

Traffic signals: US tightens border with Mexico

The US-Mexico border is the world’s biggest immigration corridor. But both legal and illegal immigration have slowed. In the 1990s, more than 500,000 migrants a year crossed into the US from Mexico. Since 2010, that number has fallen below 200,000 a year, according to UN data.

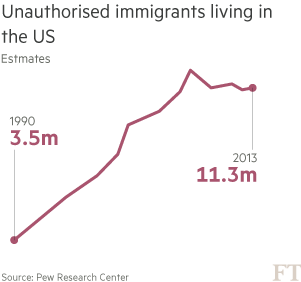

Levelling off: Downturn deters illegal workers

Illegal migration to the US has fallen in recent years – a phenomenon that some economists attribute to dwindling economic possibilities since the 2008 crisis. According to the Pew Research Center, the US’s population of illegal immigrants has stabilised just above 11m in recent years after peaking at 12.2m before the crisis.

Continental shift: EU anxieties drive churn

The crisis in the EU has caused significant churn in its migrant population. Those countries hit the hardest by the economic crisis, such as Greece and Spain, have seen significant net emigration in recent years. Countries that have done better economically, such as Germany and the UK, have attracted more migrants.

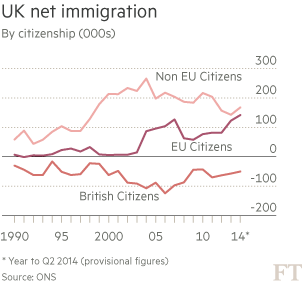

Blighty bound: UK recovery attracts EU citizens

The recovery in the UK economy has been drawing migrants back, with net migration to the UK reaching 260,000 in the year to June 2014. But the number of non-EU migrants coming to the UK has been declining, even as the number of people moving to the UK from other EU member states has been rising.

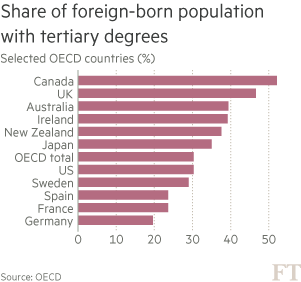

Educated and mobile: Skills are coveted

The battle is on to attract skilled migrants and it shows in the data. According to the OECD, the number of tertiary-educated migrants to its largely rich member countries has risen by 70 per cent in the past decade. Some 35m of the 115m migrants living in OECD member countries now have university degrees.

Cost concerns: Impact is broadly fiscally neutral

Opponents of rising migration say governments cannot afford the cost. Economists and business groups have long said the opposite is true: new arrivals do not just consume resources, they spend money and pay taxes. The OECD last year found that if there was a cost from new migrants it was generally small.

Comments