Healthcare: Counting the cost of cancer

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Anne Strange was too ill to dance at the evening reception when her daughter, Debbie, married in November but just being there was enough. The 63-year-old Londoner was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2010 and the disease has since spread to her liver, lungs and spine.

“All I was aiming for was to get to the wedding,” she says. “I’m so glad I did.”

Ms Strange would probably not have got there but for the Cancer Drugs Fund, a scheme within Britain’s NHS that pays for expensive oncology medicines typically used in advanced cases of the disease when often the best that can be hoped for is an extra few months of life.

Soon, even that hope will be extinguished for many after the NHS announced this week that the number of therapies covered by the fund would be cut by 30 per cent to contain spiralling costs. Among the casualties will be eribulin, made by Eisai of Japan, which Ms Strange has been taking since other treatments failed.

From a UK standpoint, the squeeze on the Cancer Drugs Fund was just another reminder of the tough choices facing the public-funded health system in an era of fiscal austerity. But it highlighted the broader global challenge posed by the rising cost of cancer care, especially medicines, as people live longer.

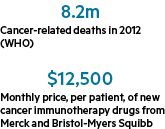

The number of over-65s on the planet is projected almost to triple between 2010 and 2050 to 1.5bn, according to the UN. This, in turn, will spur a surge in age-related diseases such as cancer. The World Health Organisation predicts the number of cases will increase 70 per cent in the next 20 years.

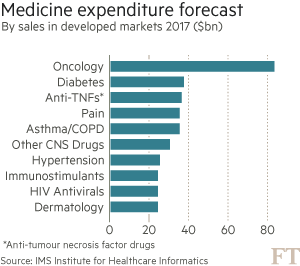

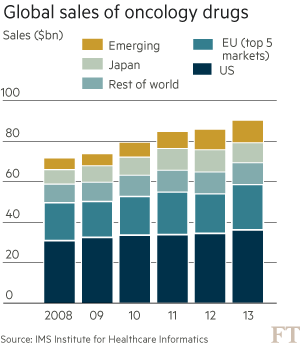

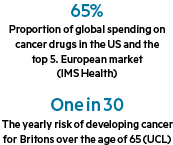

These trends are putting health systems under pressure. Global spending on cancer drugs has more than doubled in the past decade to $91bn in 2013, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. “What we’re seeing in the UK is the first manifestation of something that has been predicted for some time: the cost of these drugs is not sustainable,” says Bernard Munos, a former Eli Lilly executive and veteran industry consultant.

Pressure on US market

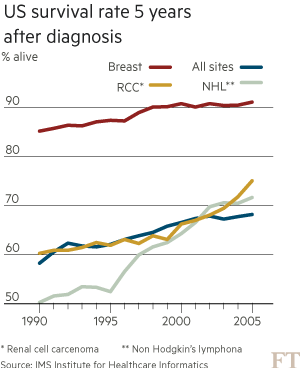

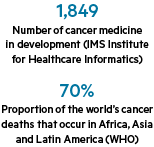

Such warnings are casting a cloud over recent medical breakthroughs that promise to revolutionise the way cancer is treated — at least for those who can afford it. More than 20 cancer drugs have been launched globally in the past two years — the strongest burst of innovation for over a decade — with an even bigger wave approaching market.

Many of them involve a new approach that aims to boost the immune system’s ability to detect and fight tumours. These so-called immunotherapies work by removing the camouflage that cancer cells use to evade the body’s disease-fighting T-cells. In clinical trials, many people who had exhausted existing treatment options have been kept alive by the new drugs for months and in some cases years.

“The whole immuno-oncology area is exploding,” says John LaMattina, former head of research and development for Pfizer. “We are heading towards a world where cancer will become a chronic disease in much the same way as we have seen with diabetes and HIV.”

This vision is raising hopes for cancer patients but also for investors as the pharmaceutical industry battles to revive growth after the weak productivity and serial patent losses of recent years. Seamus Fernandez, analyst at Leerink, says the immuno-oncology market could reach $40bn in annual sales within a decade.

Yet, such bullish forecasts are based on equally aggressive pricing assumptions. Two of the first immunotherapies — Keytruda from Merck & Co and Opdivo from Bristol-Myers Squibb — were approved by US regulators last year, each carrying a price tag of $150,000 per patient, per year.

Companies say such prices are justified by the multibillion-dollar development costs and increased effectiveness. Advances in genomic science are opening the way to evermore targeted treatments compared with the “carpet bombing” of traditional chemotherapy.

Steve Miller, chief medical officer for Express Scripts, which manages prescription drug programmes on behalf of US insurers, says nobody disputes the potential benefits of these new drugs. But he insists companies must adjust their expectations of what price even the ultraliberal US market will bear. “The science has never been better but economically it is incredibly scary.”

The US has long balked at drug rationing of the kind seen in the UK; Republican critics of socialised healthcare decry as “death panels” bodies such as Britain’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence which decides whether medicines offer sufficient value for money to be adopted.

This greater freedom for drugmakers in the US explains why prices are typically 20-40 per cent higher than in Europe. But Mr Miller says companies must compromise if they are to maintain the free market status quo in a country already spending about 18 per cent of gross domestic product on healthcare. Patients are becoming more exposed to drug costs as insurers pass on a bigger share through out-of-pocket expenses. This means that, for many Americans, a cancer diagnosis is a financial as well as medical crisis. “We believe in a free market solution for the US,” says Mr Miller. “But we need to create a sustainable system.”

There have been some examples of pressure being successfully applied. When doctors at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York refused to use Sanofi’s Zaltrap colon cancer drug in 2012 because it cost twice as much as a rival product, the company backed down and halved the price.

“What is happening in the UK today will happen in America tomorrow,” says Mr Munos. “The pressure is going to be the same from payers whether they are governments in Europe or US insurers.”

Attempts to rein in US prices will be cheered from across the Atlantic by Mark Harries, a consultant oncologist at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS trust in London. He routinely prescribes some of the medicines which will no longer be funded by the NHS for new patients from March. “We all suffer from the traditional model where the price that the market will bear in America sets the benchmark for the world,” he says.

Cancer-hunting army

Developing countries too face a struggle to contain rising cancer costs. Already 60 per cent of new annual cases are in Asia, Africa and Latin America, according to the WHO. This proportion will increase as growing wealth brings more risk factors such as sedentary lifestyles and greater longevity.

It took more than 100 years for the proportion of over-65s in France to increase from 7 per cent to 14 per cent of the population. China and Brazil are on course to make that leap within a single generation.

Access to the most advanced oncology medicines in the developing world has so far been limited. But as nascent public health insurance schemes widen and cancer rates increase, tensions over drug costs are inevitable.

“Pricing pressure is enormous in the developed and developing markets and that will only go up as people get older,” says Severin Schwan, chief executive of Roche, the world’s biggest cancer drugmaker. “The relative spend of healthcare versus overall budgets is increasing, whether politicians want to hear it or not.”

Roche and AstraZeneca are racing to catch Merck and Bristol-Myers Squibb in the first wave of immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors, which remove the brake that holds back T-cells from attacking tumours. Novartis, meanwhile, is leading a different approach that involves extracting white blood cells from patients and re-engineering them in a laboratory. These modified cells are then reinfused into the blood stream where they proliferate into a cancer-hunting army.

The first human treated with the Novartis therapy, known as Cart-19, was a six-year-old from Pennsylvania called Emily Whitehead suffering from a deadly form of leukaemia which was failing to respond to existing medicines. Nearly three years later, she is alive and cancer free. There is still much to prove but other children have shown similar recoveries in subsequent trials.

“If the innovation is big enough, I think societies will continue to reward it,” says Mr Schwan. “You will only survive in this industry in the long term if you bring truly clinically meaningful innovation or if you are a low-cost generic provider. Anything in between will disappear.”

Hagop Kantarjian, a leukaemia specialist at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Texas, argues that no amount of innovation can justify the doubling in average US prices over the past decade to more than $100,000.

“It is profiteering and greed,” he says. “If pharma companies continue on this path they will kill the goose that laid the golden egg.”

Such arguments are disputed by industry leaders who point out that gross profit margins have come down in the past decade. They say the rise of biosimilars — cheaper copycat versions of modern biological drugs — will help control costs as the previous wave of blockbuster cancer therapies from a decade ago, such as Novartis’s leukaemia drug Gleevec, begin to lose patent protection.

But Mr Munos says this does nothing to address the high price of the latest generation of products. The answer, he argues, is to break up inefficient R&D operations and outsource innovation to nimbler biotech companies — a prescription big pharma is already embracing. “The only durable solution is to make drugs more affordable and the only way to do that is to take waste out of the industry.”

Others say there is too much focus on pharmaceuticals. Money would be better used, they argue, on measures to reduce the 30 per cent of cancers the WHO says could be prevented with lifestyle changes such as stopping smoking or losing weight. A study by the Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine this week suggested a daily dose of aspirin taken by everyone in their 50s could reduce deaths from some cancers by up to 50 per cent. In other words a 19th-century medicine could have a bigger impact than modern drugs at a fraction of the price.

None of this helps those who go on to develop the disease. Mr LaMattina predicts that societies will be willing to pay a high premium for drugs capable of extending lives by years but they will become more accepting of decisions such as the one made in the UK to scrap those offering weaker benefits.

Richard Smith, a former editor of the British Medical Journal, argued last month that patients should be wary of “overambitious oncologists” and rely more on “love, morphine and whisky” in the final months of life. Better to die of cancer, he said, than a slow decline from organ failure or dementia.

But try telling that to Ms Strange, who is convinced that medicines soon to be removed from the NHS have given her an extra 18 months of life. “I’m grateful when my eyes open in the morning,” she says. “It’s just a shame that other people are not going to benefit from these drugs in the way I have.”

***

Healthcare policy: UK rationing offers a taste of things to come

For global pharmaceuticals groups, this week’s decision to remove more than a dozen cancer drugs from the NHS in England reinforced their impression of the UK as a hostile place to do business.

“We need stable, predictable healthcare policies to support investment and we are not seeing that in the UK,” says Haruo Naito, chief executive of Eisai, the Japanese drugmaker whose eribulin breast cancer medicine was cut.

Yet, in private, industry executives grudgingly accept that the UK provides a taste of things to come as countries around the world struggle to rein in healthcare costs.

Companies seeking access for a new drug to the NHS’s 64m patients must first convince England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) and similar bodies in Scotland and Wales of its cost-effectiveness. In the case of expensive cancer drugs, the verdict has often been negative.

This created a political problem for ministers fearful of headlines about patients being denied life-extending treatments. Their solution was to set up a Cancer Drugs Fund to provide extra money but its spending has soared — leading to this week’s cuts.

A government review is planned to look at whether greater flexibility can be injected into Nice’s cost-benefit calculations to allow approval of more cancer drugs. But nobody expects price pressure to ease in a country facing an annual £30bn health funding gap by 2020.

Other countries are looking to the UK for lessons. Nice has an international consulting arm and health economists at York university have become global authorities on measurement of “quality-adjusted life years” to value drugs.

There are even signs of private insurers testing the taboo that has traditionally surrounded rationing of medicines on cost grounds in the US. Express Scripts, which negotiates with drug companies on behalf of many insurers, has led a push to force cuts in the price of hepatitis C treatments by shutting out higher-priced products. Steve Miller, the company’s chief medical officer, says: “We’re closely following what Nice is doing.”

This UK influence irks Severin Schwan, chief executive of Roche, the Swiss drugmaker. “What is right for the UK is not necessarily right for everyone else.”

Comments